Introduction

Insufficient oral hygiene in children results in dental complications, including severe dental caries and gingivitis which can adversely affect a child's educational performance, self-esteem, and general health [

1-

3]. However, sufficient oral hygiene management can be challenging for children with special healthcare needs (SHCN), who encounter barriers to dental care, such as communication difficulties, limited accessibility, reliance on caregivers, and presence of underlying medical conditions [

4-

6].

As a result, children with SHCN experience a higher prevalence of untreated dental issues, which have been reported in several studies. Lewis (2009) [

7] reported that 8.1% of children with SHCN have unmet dental needs. Also, Havercamp et al. (2004) [

4] found that 14.4% of patients with intellectual disabilities had not received dental treatment in the past five years, compared to only 8% of the general population. Furthermore, according to research by Jeong et al. (2008) [

8], children with disabilities tend to exhibit challenges in managing oral hygiene, often showing poorer oral hygiene conditions compared to children without disabilities.

Therefore, for children with SHCN, daily oral hygiene management is critical to prevent severe dental conditions [

9]. Schools are in a crucial position to address this need by offering consistent oral health monitoring and support, which have been shown to reduce dental disease and promote long-term oral health [

10-

12]. In South Korea, the government has introduced oral health offices in special schools to provide routine dental care to children with SHCN [

13]. However, as of 2015, the number of these offices remained below the target set by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, leaving children in special schools without sufficient dental care [

14].

Therefore, this study aimed to analyze the differences in the oral health office systems related to the dental examination results of the two special schools and to assess their impact on oral health indicators. This research may provide evidence-based recommendations for enhancing oral health policies in special school settings.

Materials and Methods

This study received approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the Jeonbuk National University Hospital (IRB No: 2024-11-014).

This study analyzed dental examination data from Dongamchadol school and Eunhwa school, provided by the Jeonju Public Health Center. At each school, a single epidemiologist conducted a biannual dental examination. During the examination, students were seated in a dental chair, plaque control was performed, and an oral examination followed.

In 2023, Eunhwa school had 146 enrolled students. Among them, 61.0% had intellectual disabilities, 29.5% had autism spectrum disorders, and 8.9% had physical disabilities, including cerebral palsy. Dongamchadol school had 122 students in the same year, with intellectual disabilities at 55.0%, physical disabilities including cerebral palsy at 31.1%, and autism spectrum disorders at 8.2%.

The data for Dongamchadol school ranges from middle 2019 to middle 2023, while Eunhwa school's data ranges from early 2015 to middle 2023. However, some data points were unavailable due to the COVID-19 pandemic: middle 2021 data for Dongamchadol school and data from early 2018 to early 2022 for Eunhwa school were missing. The number of students and permanent teeth examined each period are shown in

Table 1.

The primary variables included the decayed, missing, and filled teeth (DMFT) index, decayed, missing, and filled (DMF) rate, decayed teeth (DT) rate, missing teeth (MT) rate, and filled teeth (FT) rate. Longitudinal changes in these metrics were analyzed separately for each school to observe trends over time. Furthermore, during overlapping data collection periods, a cross-sectional analysis was performed to compare dental health patterns between Dongamchadol and Eunhwa school.

Results

Dongamchadol school

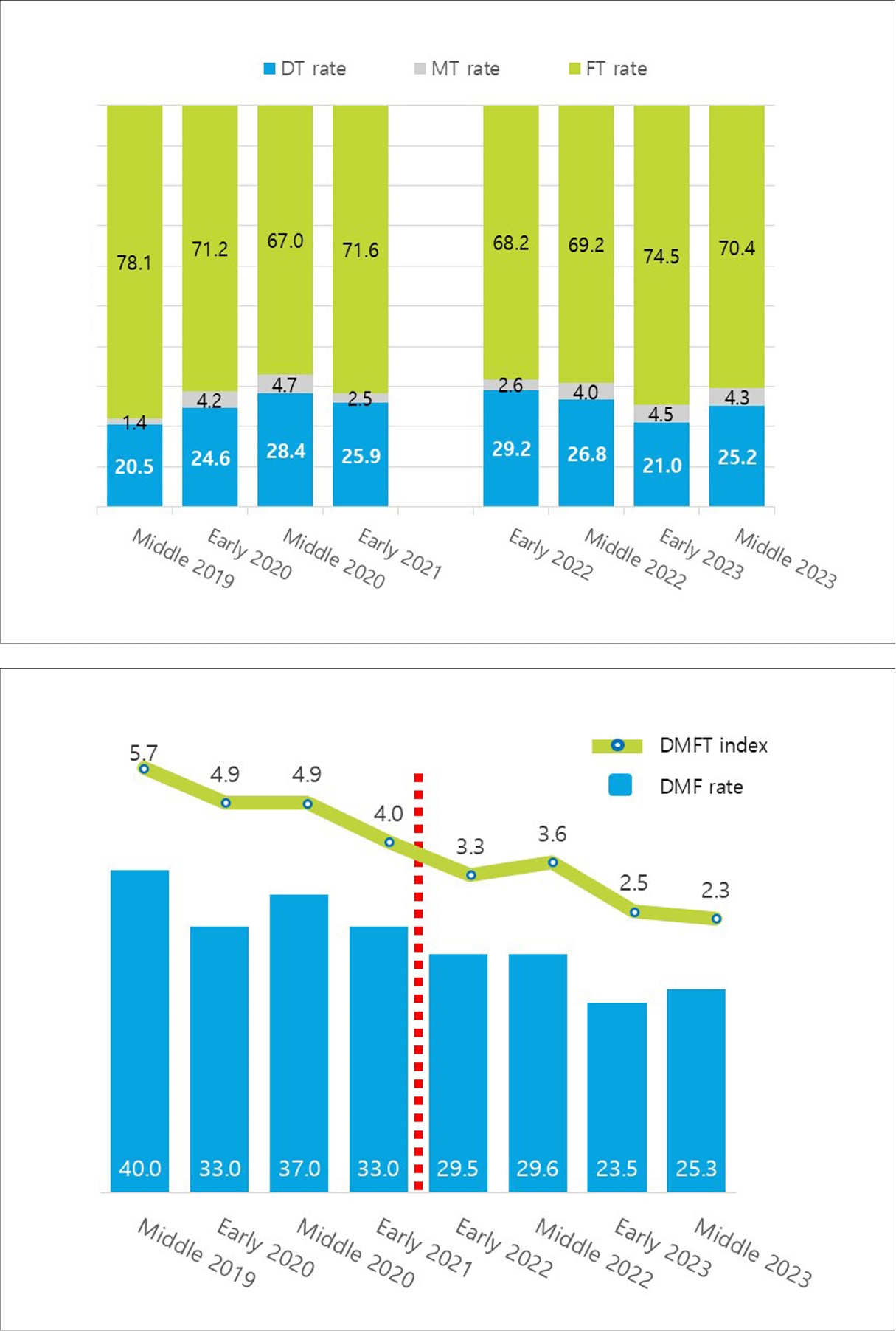

The DT, MT, and FT rates at Dongamchadol school remained relatively stable from middle 2019 to middle 2023, despite the COVID-19 pandemic. The DT rate ranged from 20.5% to 29.2%, while the FT rate remained between 67.0% to 78.1%. The MT rate was consistently low, fluctuating only slightly between 1.4% and 4.7% (

Fig. 1A).

Additionally, the DMFT index showed a decreasing trend, dropping from 5.7 in middle 2019 to 2.3 in middle 2023. Similarly, the DMF rate exhibited a declining trend, decreasing from 40.0% in middle 2019 to 25.3% in middle 2023, indicating consistent improvements over time (

Fig. 1B).

Eunhwa school

The DT, MT, and FT rates at Eunhwa school exhibited notable fluctuations over the observation period from early 2015 to middle 2023, especially before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. The FT rate was relatively high, ranging from 76.2% to 91.9%, but it experienced a sharp decline to 56.9% in middle 2022 before rebounding to 90.2% in middle 2023. The MT rate, on the other hand, remained consistently low, fluctuating slightly but staying below 5% throughout the period (

Fig. 2A).

The DMFT index at Eunhwa school stayed within the range of 6.8 to 7.7 before the pandemic but dropped to 5.4 in middle 2022. A similar trend was observed in the DMF rate, which was high at 83.8% to 91.1% from early 2015 to middle 2017 but decreased significantly to 75.6% in middle 2022 and further declined to 20.2% by middle 2023 (

Fig. 2B).

Comparison between Eunhwa and Dongamchadol schools

Over the observation period, the DMFT index was consistently higher at Eunhwa school compared to Dongamchadol school. The DMF rate at Dongamchadol school remained relatively stable, decreasing slightly from 29.6% in 2022 to 25.3% by middle 2023. In contrast, Eunhwa school experienced significant fluctuations, starting at 75.6% in middle 2022, dropping sharply to 33.1% in early 2023, and further decreasing to 20.2% by middle 2023, ultimately falling below the rate observed at Dongamchadol school (

Figs. 1B and

2B).

Discussion

This study analyzed dental examination data from two special schools in Jeonju. The DMF rate and DMFT index in Eunhwa school fluctuated while Dongamchadol school had relatively stable outcomes. These disparities appear to be influenced by workforce structure, treatment frequency, and external medical support.

Dongamchadol school, a private institution, has maintained a stable workforce, with a dental hygienist working for 17 years and a dentist consistently providing monthly care for 8 years. This continuity allows for consistent monitoring and personalized treatment. In contrast, Eunhwa school, a public institution, relies on weekly dental services from rotating dentists, supported by two dental hygienists. While this ensures regular intervention, frequent staff turnover may affect continuity of care.

Differences in treatment frequency further contribute to the variations. Dongamchadol school provides monthly dental care with a focus on caries prevention and treatment, while Eunhwa school offers weekly services, including scaling, fluoride application, extractions, and restorations, alongside an emergency call system. However, changes in school leadership and staff have affected service stability, as the principal’s and staff’s commitment to oral health management directly influences program consistency. Leadership transitions have sometimes led to weaker implementation or temporary reductions in weekly care services. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Eunhwa school halted dental care entirely in strict compliance with government policies, further impacting oral health outcomes.

External medical support also differs significantly. Dongamchadol school can secure private donations more easily, allowing for flexible funding and stable programs. In contrast, Eunhwa school must navigate strict governmental procedures to secure external funding, limiting its ability to implement independently funded programs. However, as a public school, it receives regular government funding, ensuring baseline financial support.

In comparison with the national figures, the South Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (2012–2022) reported a national average DMFT index of 1.94 and a DMF rate of 58.4% for 12-year-olds [

15]. In comparison, both Dongamchadol and Eunhwa schools exhibited higher DMFT index, reflecting a greater number of decayed, missing, or filled teeth per student. However, the DMF rate observed in this study was approximately half the national average, indicating a fewer number of students with experience of dental decay. This discrepancy can be explained by consistent management in special schools, which is likely to reduce the prevalence of dental decay among long-term enrolled students. In contrast, newly enrolled students often are present with higher levels of decay. The findings underscore the efficiency of long-term oral health management in special schools.

When comparing the DMF rate in this study to the data on special health care needs (SHCN) provided by the Ministry of Welfare of South Korea in 2015, which reported 33.3% for six-year-olds and 85.2% for twelve-year-olds, both Dongamchadol and Eunhwa schools revealed lower rates [

16]. In a study conducted among 200 SHCN in Jinju with a high rate of special school students aged 6-29, the DMF rate was 65.0% in 2008 [

17]. This indicates that the oral health programs in these two special schools are effective and are showing improvements in rates in addressing the oral hygiene needs of students.

In an international context, the DMFT index in this study is slightly higher compared to findings from other countries. Research from 1283 students with SHCN aged 6-16 years in Germany reported a DMFT index of 1.4 ± 2.6 for children aged 6-16 [

18]. In a study of 3562 children with SHCNS attending schools in Birmingham, United Kingdom, found a mean DMFT index of 1.85 for 11.9-year-olds [

19]. Another survey of 136 students aged 2-26 attending a special school in Turkey had a DMFT index of 1.58±2.72 [

20]. This suggests that although the oral health offices in these two special schools are effective, further improvements are needed to align with global trends. However, caution is needed when making cross-national comparisons, as differences in factors such as age range, types of disabilities, and differences in epidemiologists can significantly influence outcomes.

The significance of this study is evaluation of factors affecting oral health offices in special schools. However, there are certain limitations. First, limited sample size including only two schools, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Second, data collection was affected by external factors such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Lastly, the study did not account for disability types, socioeconomic factors or residential types.

Future research should include a larger comparison group, with schools of similar sizes across South Korea and internationally over an extended period. It should also examine differences between students such as living at home versus care facilities, economic backgrounds, and oral health rates based on specific disabilities. These efforts would provide a more comprehensive understanding of oral health disparities in special school populations.

The comparison between Dongamchadol and Eunhwa schools highlights the importance of stable staffing, leadership commitment, and adaptable funding in maintaining effective oral health programs for students with special healthcare needs. Ensuring continuous management through consistent oral health care policies seems essential for improving and sustaining oral health outcomes in special schools.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print